BAGHDAD — Pope Francis on Monday wrapped up his historic whirlwind tour of Iraq that sought to bring hope to the country’s marginalized Christian minority with a message of coexistence, forgiveness and peace.

The pontiff and his traveling delegation were seen off with a farewell ceremony at the Baghdad airport, from where he left for Rome following a four-day papal visit that has covered five provinces across Iraq.

As the pope’s plane took off, Iraqi President Barham Salih was at hand on the tarmac, waving goodbye.

At every turn of his trip, Francis urged Iraqis to embrace diversity — from Najaf in the south, where he held a historic face-to-face meeting with powerful Shiite cleric Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, to Nineveh to the north, where he met with Christian victims of the Islamic State group’s terror and heard their testimonies of survival.

The pontiff’s visit witnessed scenes unimaginable in war-ravaged Iraq just a few years ago.

In Iraq’s south, Francis convened a meeting of Iraqi religious leaders in the deserts near a symbol of the country’s ancient past — the 6,000-year-old ziggurat in the Plains of Ur, also thought to be the birthplace of Abraham, the biblical patriarch revered by Jews, Christians and Muslims. The gathering brought religious representatives across the country rarely seen together, from Muslims, Christians, Yazidis and Mandaeans. The joint appearance by figures from across Iraq’s sectarian spectrum was almost unheard-of, given their communities’ often bitter divisions.

The pope called on them to work together and make peace.

In the city of Najaf, Francis held a private meeting with the notoriously reclusive al-Sistani, among the most influential and revered Shiite clerics, and together they delivered a powerful message of peaceful coexistence and affirmed the rights of Iraqi Christians. It was a powerful message the Vatican hopes can preserve the place of the thinning Christian population in the tapestry.

Al-Sistani is one of the most senior clerics in Shiite Islam, deeply revered among Shiites in Iraq and worldwide. His rare but powerful political interventions have helped shape present-day Iraq. Their meeting in al-Sistani’s humble home, the first ever between a pope and a grand ayatollah, was months in the making, with every detail painstakingly negotiated beforehand.

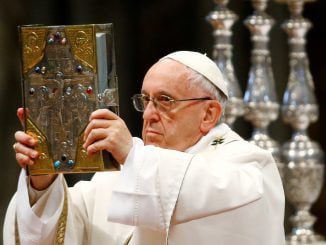

In the northern city of Mosul, once at the heart of the IS militants’ so-called Islamic “caliphate” and still devastated years after the Islamic State group’s onslaught, Francis prayed in a square containing the remnants of four churches — Syriac Catholic, Armenian Orthodox, Syriac Orthodox and Chaldean — nearly destroyed in the war to oust IS from the city.

Later, in the Christian town of Qaraqosh, where an entire Christian community was forced out by the brutality of IS militants, Francis urged Christians to forgive their oppressors and rebuild their lives.

People gathered in crowds to catch a glimpse of the pope wherever he went, fueling coronavirus concerns. Few wore facemasks, especially during Francis’ stops in northern Iraq on Sunday. That day ended with an open-air mass in a stadium that drew nearly 10,000 people. Security was tight and most events were strictly controlled.

Public health experts had expressed concerns ahead of the trip that large gatherings could serve as superspreader events for the coronavirus in a country suffering from a worsening outbreak where few have been vaccinated. The pope and members of his delegation have been vaccinated but most Iraqis have not.