RALEIGH — For some, coaching is a profession. For Bill Hayes, it was a calling.

That’s why he decided to jump off the ladder of mainstream opportunity just as he began climbing it in 1976 to take the head coaching job at Winston-Salem State.

Some, including his wife, considered the move a step down from his position at Wake Forest, where he became the first African-American assistant coach in ACC history. But it quickly became a passion for Hayes, who spent the rest of his career toiling and winning in relative anonymity at historically black colleges.

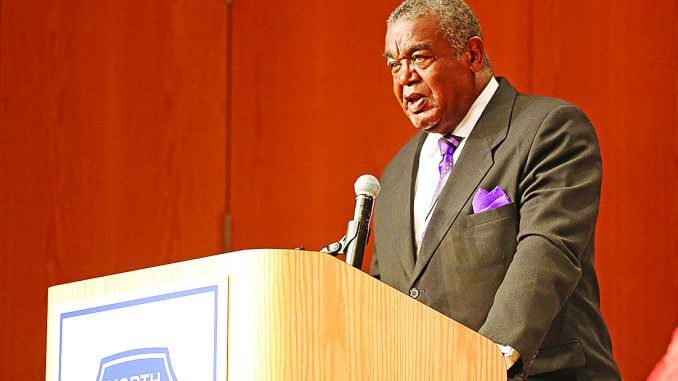

“I remember when I was at Wake Forest, and Winston-Salem State asked me to come be the head football coach. It was crazy,” Hayes said earlier this month when he was inducted as one of the newest members of the N.C. Sports Hall of Fame.

“I had to take a pay cut. My wife said, ‘Are you an idiot?’ But I just had a sense in my heart and soul that those kids needed a guy like me, a guy that was going to be there every day and give them a full day’s work.”

Hayes fulfilled that obligation to his players and then some while going on to become the winningest coach ever at both Winston-Salem State and NC A&T.

He compiled 195 victories over 27 seasons before moving into administration in 1987, winning three CIAA titles and three MEAC championships, to go along with Historically Black Colleges and Universities national crowns in 1990 and ’99. He also sent several players to the NFL.

Hayes has earned his share of recognition for his accomplishments, including induction into seven other halls of fame along the way. But it hasn’t been the kind of acclaim he might have gotten had he recorded the same success at Power 5 programs.

It’s a fact that was driven home in 1977 when Hayes was named as the national small college Coach of the Year, the same year Lou Holtz won the award in the major college division.

“I’m on the stage at a convention with 8,000 coaches, and it’s me and Lou Holtz, two old North Carolina guys,” Hayes said. “I didn’t get the kind of credit Lou Holtz got and didn’t make that kind of money, either. But I was there.”

It was an eye-opening experience that could easily have led Hayes to reconsider his commitment to the HBCU ideal.

Instead, it only reminded him of how important it was to him.

Not that he didn’t have opportunities to return to the ACC.

“Mack Brown said, ‘Bill, why don’t you come and work with me?’ Hayes said of the former North Carolina coach. “He told me this back in the ’70s and ’80s. He said, ‘I don’t know why you waste your time at those schools.’

“But those kids needed me, a hard-charging guy, no-nonsense, highly disciplined, got-to-play-by-the-rules guy. That’s what they needed. That’s what I gave them. So God put me there. It wasn’t my choice.”

Even if it was, he probably wouldn’t have changed a thing. He knew from experience that the turf wasn’t necessarily greener on the other side of the college football hill.

Although times and social attitudes changed and improved as his career progressed, Hayes knew from his experience during the early ’70s that it wasn’t always easy being a black coach at a school in the Deep South.

“It was a challenge, but I enjoyed it,” he said. “I just knew that I had to outwork everybody, that’s all. When (Wake Forest coach Chuck Mills) told us we each had to go out and get three blue-chippers, I’d get 10. If coach said we’re going to be in at 7 o’clock in the morning, I’m going to get there at a quarter past 6. I knew what it was like. I knew who I was. I knew what I had to overcome, and I did it.”

That success is admittedly his most cherished accomplishment.

He’s especially proud of the fact that, even as HBCU schools have begun to assimilate into mainstream conferences and diminish in significance, the three programs for which he is most associated — Winston-Salem State, A&T and NC Central (where he served as athletic director) — are still among the best and most respected in the business.

His association with those schools may not have earned him a fortune, but at the age of 74, it continues to bring him fame.

“This is as good as it gets,” Hayes said of his latest honor. “It says it all to be in your state’s hall of fame.”