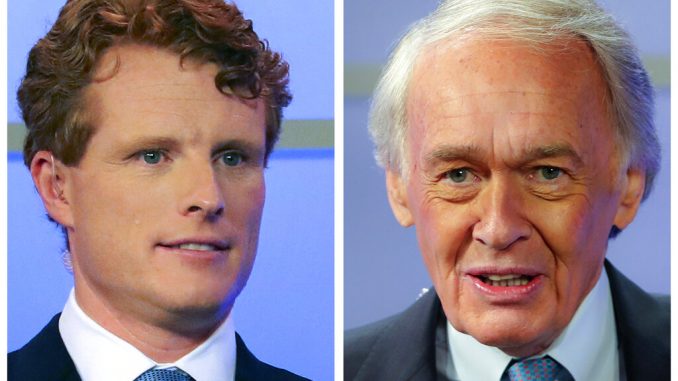

BOSTON — Perhaps inevitably, the long political shadow of the Kennedy family is hovering over an increasingly acrimonious contest between U.S. Sen. Edward Markey and U.S. Rep. Joe Kennedy lll, who’s hoping to oust the incumbent in next week’s Democratic primary in Massachusetts.

At first, Kennedy shied away from leaning too heavily into a family history that includes former President John F. Kennedy, former U.S. Senator and U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy — his grandfather — and former U.S. Sen. Edward Kennedy, who held a Senate seat in Massachusetts for nearly half a century until his death in 2009.

Kennedy said he began discussing his family in response to Markey, who during one debate told Kennedy he should tell his father — former U.S. Rep. Joe Kennedy II — not to help fund a political action committee that was going after Markey.

Kennedy backers also are irked by Markey’s decision to paraphrase a famous JFK quote in an online ad, saying, “We asked what we could do for our country. We went out, we did it. With all due respect, it’s time to start asking what your country can do for you.”

“If he wants to talk about the Kennedys, then I will talk about the Kennedys,” Kennedy responded on City Hall Plaza, steps away from a federal building named after President Kennedy.

Kennedy went on to list what he saw as Kennedy family highlights, from JFK’s early work on the Civil Rights Act to his grandfather’s decision to send federal marshals to protect freedom riders in the 1960s.

Kennedy has also denounced what he said were social media attacks from Markey backers.

During one tense debate exchange, Kennedy said supporters of Markey “have put out tweets saying that Lee Harvey got the wrong Kennedy” — a reference to JFK assassin Lee Harvey Oswald.

Markey called such tweets “completely unacceptable.”

Kennedy’s reference to his family history has prompted Markey to recall his own family story growing up in working-class Malden, where his father drove a truck for the Hood Milk Co.

“I could see my mother and father trying to figure out how to pay the bills at the kitchen table,” Markey said. “I know that families all across Massachusetts are struggling with those bills right now.”

Ironically, the weight of the Kennedy legacy has helped Markey, first elected to Congress in 1976, position himself as an underdog and a progressive firebrand. He’s been endorsed by New York Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, with whom he teamed up to introduce the Green New Deal climate change initiative.

Kennedy, promising a new generation of leadership, also picked up a high-profile endorsement, but from a more establishment figure: Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

Pelosi’s embrace of Kennedy has irked some supporters of Markey, who were angry at her decision to endorse in a Democratic primary.

Kennedy also has tried to portray Markey as tone deaf on the issue of racial inequity, criticizing his initial opposition to school desegregation efforts in Boston in the 1970s and pointing to the father of Danroy “DJ” Henry, a young black man from Massachusetts killed by police 10 years ago. Henry’s father criticized Markey, saying he failed to help the family seek justice.

Markey said he has apologized to the Henry family and signed a letter seeking a federal Justice Department investigation into the killing. “The Henry family deserves justice,” he said during a recent debate.

Markey, in turn, has tried to portray Kennedy as “progressive in name only,” faulting him for deciding early in his career to work as a prosecutor for Michael O’Keefe, a Republican district attorney.

“He could have worked for anyone. He could have worked for the Innocence Project,” Markey said. “But instead he decided to go and work for a right-wing Republican.”

Despite the verbal sparring, the two largely agree on many issues, from abolishing the Electoral College to extending benefits to immigrants in the country illegally who lost jobs in the pandemic. Both have also stopped short of calling for defunding police departments, but have said there’s a need to balance spending on police and other needs such as schools.

A poll released Wednesday by the UMass Lowell Center for Public Opinion found 52% of respondents supported Markey and 40% backed Kennedy, with 6% undecided and 2% favoring another candidate. That was outside the poll’s margin of error of 4.1 percentage points.

A second poll by Suffolk University released Wednesday found a 10-point lead for Markey, also outside the poll’s margin of error of 4.4 percentage points.

Whoever wins will head into a general election contest in a district that has historically favored Democrats. The candidate will face the winner of a low-key GOP Senate primary pitting Kevin O’Connor, a lawyer, against fellow Republican Shiva Ayyadurai, who ran a failed campaign for Senate in 2018.

Early on, Markey and Kennedy were forced to grapple with the coronavirus, which barred them from knocking on doors, shaking hands or holding rallies.

Instead, the campaigns retreated online — holding virtual rallies, virtual endorsements and virtual fundraisers. As Massachusetts began to reopen, they began more traditional campaigning with social distancing and face masks.

The pandemic has also shaken up the voting process.

While primary day is Tuesday, many voters have already cast their ballots at early voting locations or by mailing them or depositing them in drop boxes. At least 1 million registered voters in Massachusetts requested mail-in ballots this year.